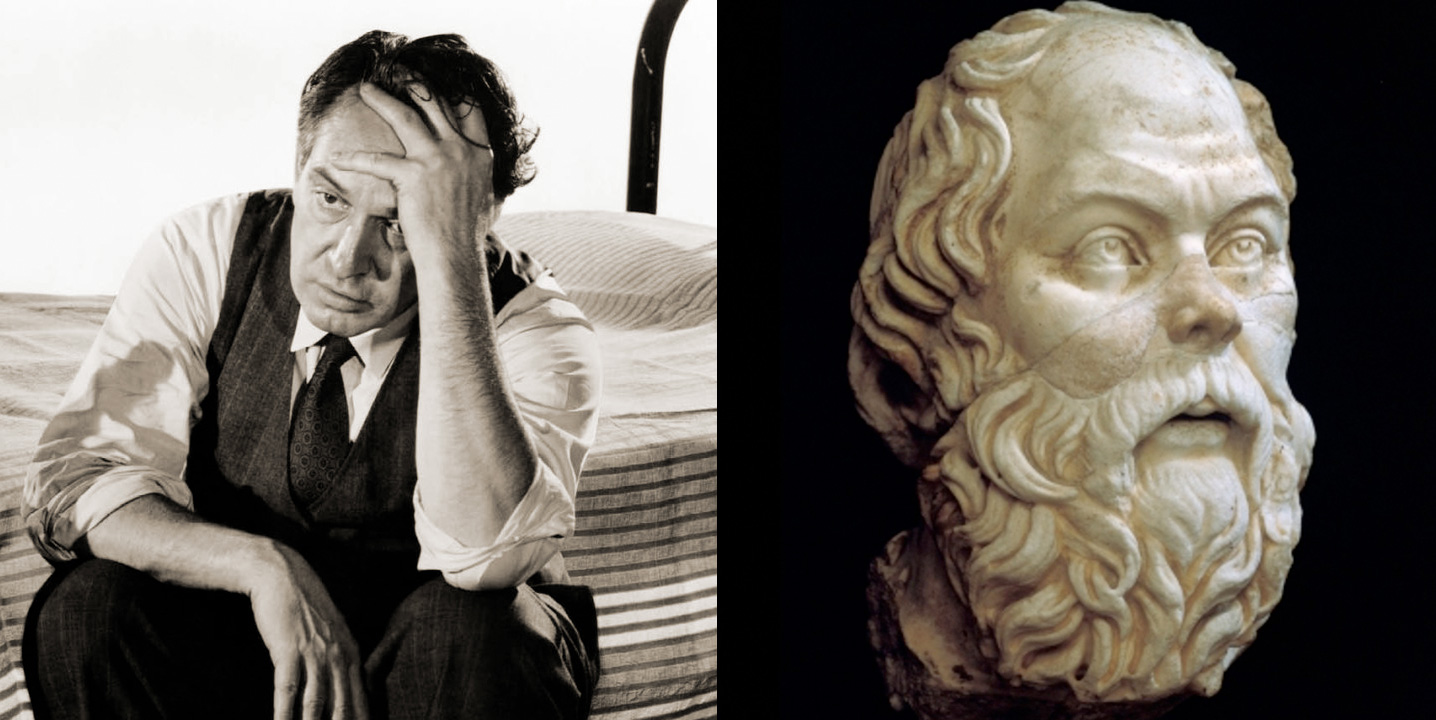

The only thing you got in this world is what you can sell

—Arthur Miller, Death of a Salesman

The unexamined life is not worth living.

—Plato, Apologia

Who earns your trust—the salesman on commission? The copywriter turning a phrase? The anonymous online reviewer? The targeted social media ad?

Would you have trusted the Sophists, who in ancient Greece taught rhetoric, holding the power to persuade as their highest goal?

Or would you have trusted the philosophers, who fought for objective truth, even if it meant telling you something you really didn’t want to hear?

In antiquity, orators competed for the minds of students, senators, and citizens. Mercenary practicality clashed with intellectual idealism. Today we face spin, propaganda, social media disinformation campaigns, and all varieties of fake news. The fight continues.

The simple questions, then and now: does an argument serve truth, or only its speaker? How can we know?

Socrates approached these questions through the analytic techniques of his dialogues. He proposed little, but held everyone to the highest standards of logic and intellectual honesty. He inspired Plato to propose a radical solution to the problems of truth-seeking (and by extension, all other problems): government lead by a Philosopher-King.

This political system has not exactly taken off. Socrates’ brand of rubbing debaters’ noses in their own fallacies didn’t work out too well for him personally, either.

The Sophists’ approach seems to have done better, if not in the marketplace of ideas, then certainly in the plain old marketplace. Around 1700 years after Socrates was executed, the sophists’ legacy found a comfortable home in the English language, in the word sophistry:

1. Specious or fallacious reasoning; employment of arguments which are intentionally deceptive.

2. The use or practice of specious reasoning as an art or dialectic exercise.

3. Cunning, trickery, craft.

500 years later, our language found improvement in a more concise, Germanic synonym:

Bullshit.

It could be argued that the Sophists’ victory means a loss for more than just the poor philosophers.

In his 2005 book On Bullshit, Princeton philosophy professor Harry Frankfurt examines his subject in relation to truth and lies—along with humbug, balderdash, claptrap, hokum, drivel, buncombe, imposture, and quackery. If I had to summarize his book in one statement it would be:

The liar and the truth-teller are closer to each other than to the bullshitter—because they’re both deeply concerned with the truth. The bullshitter, however, is concerned with moving you to an action, belief, or impression. But doesn’t give a shit about the truth.

In the worlds of advertising, marketing, and branding, Frankfurt’s definition of a bullshitter reads like a boilerplate job description.

I have a bit of a problem with this, as should you. If you’re a philosopher at heart, the problem will be that you care about the truth. If you’re a sophist, the problem will be more pragmatic: the other sophists have exhausted the innocence and good will of the people. Nearly everyone knows you’re full of shit. This makes your job difficult.

So what’s a poor professional sophist to do? A common solution is to bullshit more, and from all angles (360 campaigns!) and to hit your marks with ever-greater precission, right between the eyes (targetting through ad networks, browser tracking, personal data mining, peeping through the digital shades at night …)

Maybe you find yourself on the receiving end of this thinking—like, every day. Does it put you in a buying mood? Does it inspire trust in the message? In whoever’s finger’s on the nuclear button of the contemporary marketing machine?

But wait—what if you’re a philosopher? What if you’re committed to the truth, and, like Socrates, use your professional rhetorical skills only in truth’s service? You may still have a problem: guilt by association. You’re using tools and media that were coopted by sophists long before you ever showed up. You probably work for sophists. You may even dress like a hipster sophist. All of this, again, makes your job difficult.

I’ve noticed that some companies have found a different path. Many seem to have found it by accident. Some may only be barely aware they’re doing anything unusual. Some might have marketing departments forging down traditional paths, while a roge operator heads in the opposite direction, much to the delight of customers. I’ve been watching examples of these phenomena over the last several years, learning everything I could from them. I’ve been benefiting both as a writer and as a customer.

I’ll discuss some of these observations in depth in my next article, Ambassadors in the Trenches: The Future of Marketing has been with us for years

© Paul Raphaelson